The London & Brighton Railway began at a junction with the London & Croydon Railway near to the present day Norwood Junction in South London. By using London & Croydon's existing track between Norwood and London Bridge Station, only 41 1/2 miles of new line had to be built to reach the south coast at Brighton. 11 3/4 further miles of the route were built and jointly owned with the South Eastern Railway, whose trains also started out from London Bridge Station but left the line at Redhill to continue eastwards on the company's own tracks to Folkstone & Dover. This arrangement came about thanks to an awkward anomoly insisted upon by Parliamentary red tape surrounding this scheme. This one proposal gave rise to 60 years of disputes between the LBR and the SER, but the overall arrangement with the other two railway companies avoided the need for further costly junctions and also ensured that the lines were well maintained due to the joint responsibility.

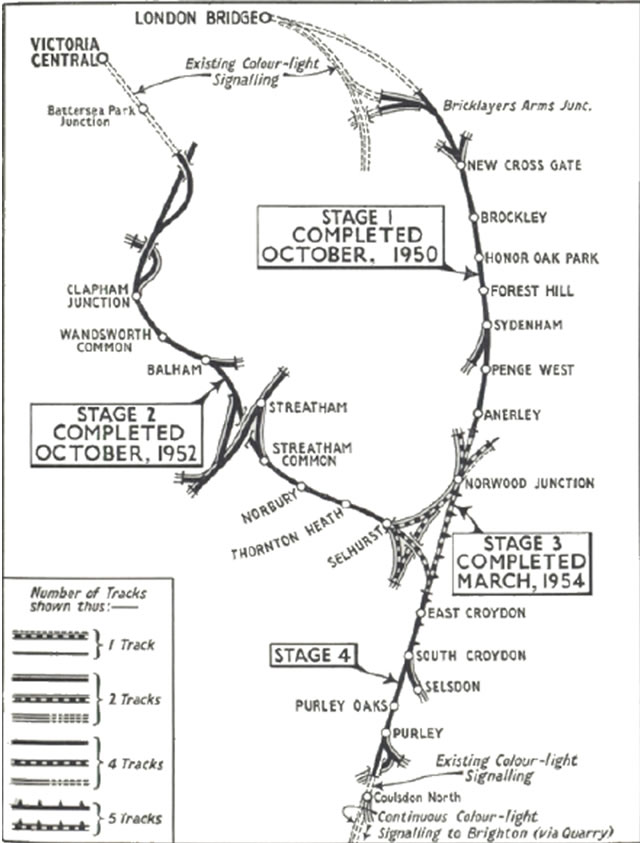

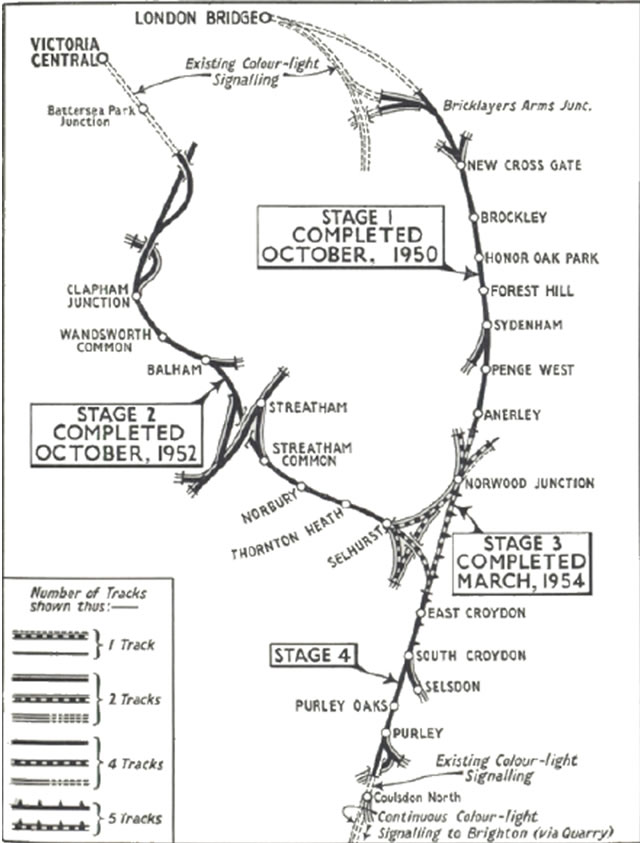

ABOVE: The map above shows coloured light signalling map reproduced above is from the 3 page document called 'Colour Light Signaling in the Norwood Triange', originally published by the Railway Magazine in May 1954. This is available in a PDF file format for further study by CLICKing on the link above. The complexity of Norwood Junction can be clearly seen, with the track towards Brighton extending southward at the bottom of the map.

As the London to Brighton line began to take shape, Engineers were also aware that the Bill had also been authorised, allowing the construction of branches to Shoreham and to Newhaven, as per the original criteria. All kinds of proposals for these two branches were published. One such proposal was a particularly interesting idea put forward by Mr. John Vallance. In June 1827 he demonstrated his Atmospheric Railway System in Brighton. This system worked by enclosing the entire railway in a tunnel and having a continuous build up of air pressure behind the train and an exhaust arrangement ahead of the train so that the drop in pressure equalisation would allow the train to be propelled forward. It was claimed that this system would allow the train to reach speeds of up to 100 mph!

A representative of the Russian Embassy was so impressed with the idea that he recommended construction of an atmospheric line from Saint Petersburg to Moscow and The Black Sea. The Brighton Vestry, however, acknowledged the merits of this scheme in a resolution dated 5th June 1827 but failed to take the idea any further, merely putting its interests on record in the minutes of the resolution. It is sad to note that nothing ever became of this scheme with regard to the London to Brighton Line: no-one came forward with financial backing for the scheme and Mr. Vallance and his technical brilliance faded from the scene.

4 out of the 5 proposed routes from London to Brighton involved construction of some tunnels. The one exception was a proposal put forward by Mr. Nicholas Cundy. This line would have branched off from the London and Southampton Railway at Wandsworth and proceed south via Leatherhead, Dorking, Horsham and Shoreham. It became known as the “London to Brighton without a tunnel Railway” but it dropped out of the competition early in the proceedings.

Mr. Rennie’s proposal had 5 tunnels of which the 2 longest were at Merstham (1830 yards) through the North Downs and also at Clayton (2260 yards) through the South Downs. A smaller tunnel near Balcombe (1133 yards) pierced the forest ridge just to the south of Crawley.

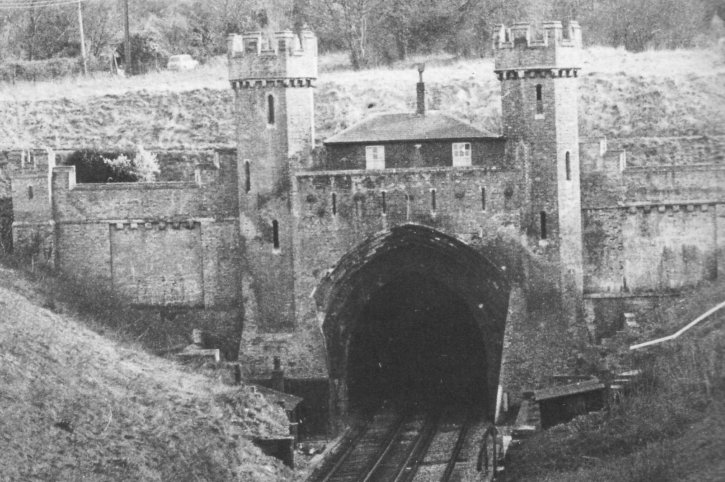

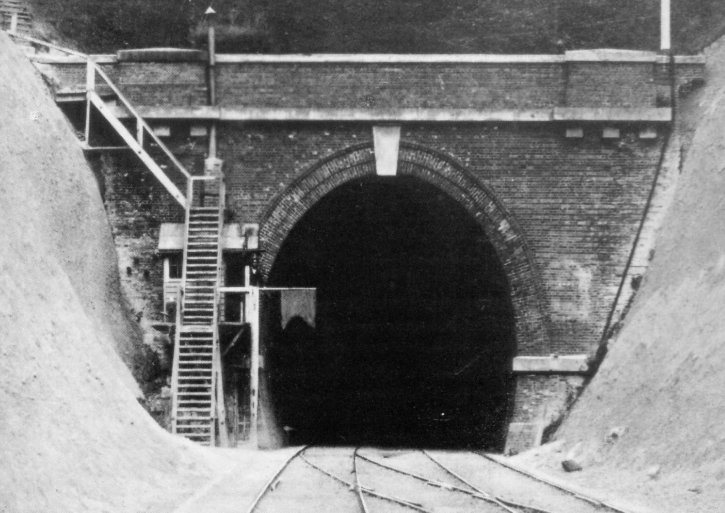

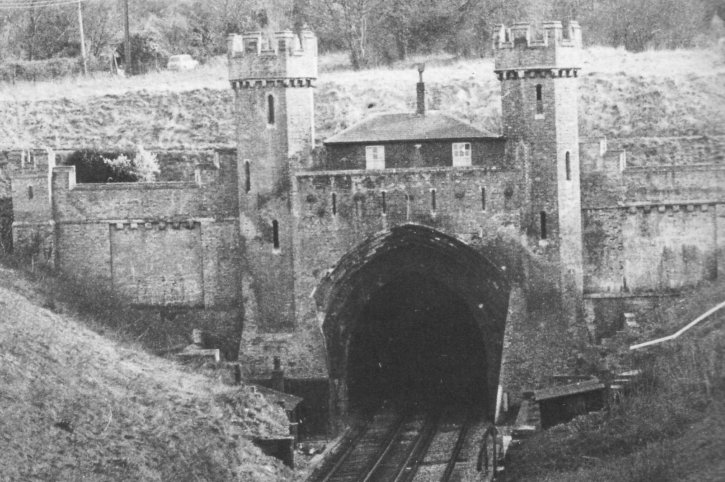

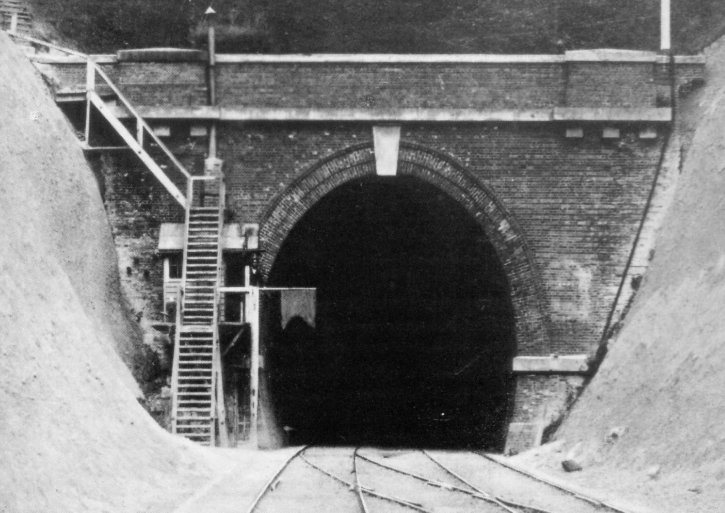

ABOVE & BELOW: These two pictures show the portals of the 2260-yard long Clayton Tunnel, which carries the London to Brighton Main Line through the South Downs. The highly ornate North Portal is shown above. For some strange reason, a bungalow has been built between the turrets adding a weird touch of domesticity to a scene that would be nicely rounded by the inclusion of a portcullis. The Southern portal shown below is a little dull by comparison. Note the tiny signal cabin and its stovepipe on the left side. The tunnel was the scene of a horrific pile-up after the signal flag was not seen in dense fog. Ghosts of those killed in the accident are said to haunt the little bungalow after the corpses were laid there for recognition. (Images owned by S.W.Stevens-Stratten/D.Cullum)

ABOVE: Another very impressive but rather overlooked masterpiece on the London to Brighton line is the Ouse Valley Viaduct, shown above. Each of the 37 piers has a different height aperture in it. Most of the millions of bricks used were bought from temporary brickfields along the River Ouse by small barges. Just visible at the far right hand end is one of the 4 ornate little temples, which mark the corners of the viaduct. (Image owned by J.Scrace)

Considerable quantities of coal, freight and building materials came to Brighton by sea. Until the harbour works at Shoreham were undertaken, these were usually unloaded onto Brighton beach. This emphasised the importance of the harbour and it is not at all suprising that the Shoreham branch was begun at the same time as the main line to London, whilst the line to Newhaven was deferred.

Being just 6 miles long and without any major civil engineering encumbrances, the Shoreham branch was completed first. It turned Eastward from Brighton Station and entered a deep cutting followed by a bridge under Chatham Place, then a little further on a tunnel under Prestonville (the area triangulated by Prestonville Road, Dyke Road and Old Shoreham Road). Montefiore Road then bridges the line before reaching Hove Station at Holland Road. This is the site of the original Hove Station, but in later years the site was moved westwards to where it currently stands.

The land between Hove and Portslade stations were originally assigned to gravel pits and brick fields so little in the way of civil engineering was required on that stretch of the route. In recent years, bridges have been created at Olive Road and Aldrington Crescent along with a small halt at Aldrington, originally named Devil's Dyke Junction.

The other intermediate stations were at Portslade, Southwick, Kingston and Ham Common on the outskirts of Shoreham (the latter in early years). While Shoreham appears to have been the intended terminus for this branch, its design is such that it appears to facilitate onward rail track. The line was shortly extended along the coast to Portsmouth.

ABOVE: This photo shows Portslade station, which is relatively unchanged in the present day save for the small entrance canopy over the approach steps, which was removed in 1891.Green’s sponge cake-mix factory stood behind the house far right in the photo, and had its own siding. (Image owned by Lens of Sutton)

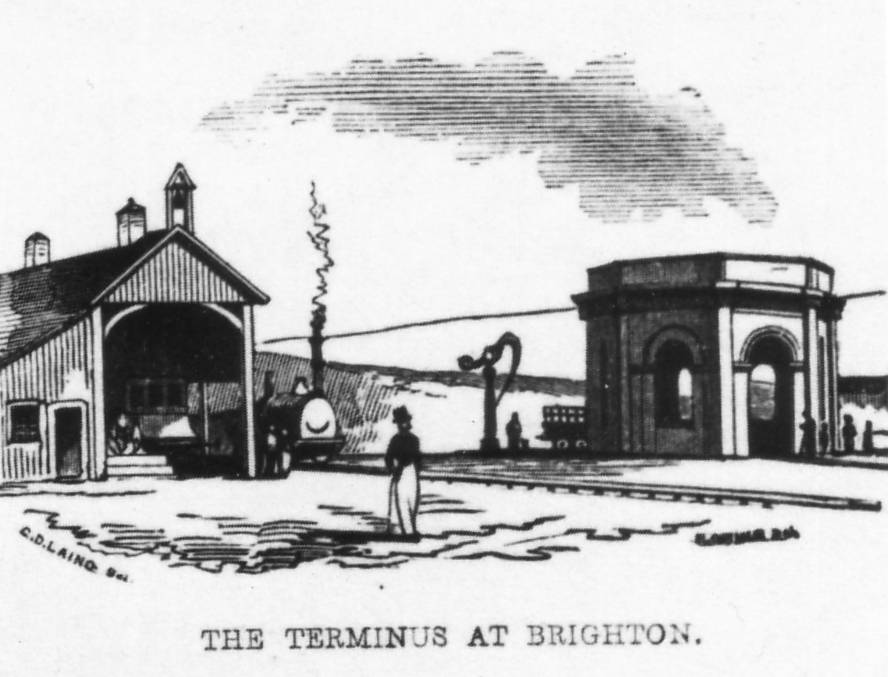

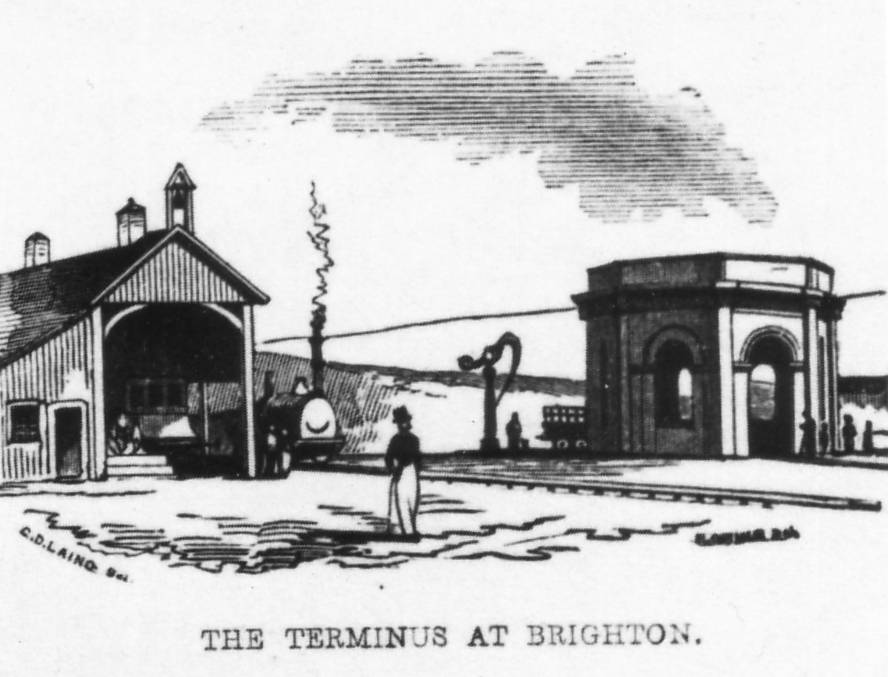

The Shoreham branch was officially opened to passenger traffic on 11th May 1840 with public services beginning the next day. The official opening was documented in the Brighton Herald along with many engravings of the event. One in particular showed the station building. It was not the grand and impressive structure that exists today, but was originally an unassuming building more akin to a glorified engine shed and appears to be upstaged by the stone built water tower (for the locomotives) next to it! Construction of Mocatta’s celebrated station building did not commence until October 1840. The only other building of note was a small building that was erected for the station clerks.

ABOVE: The original train shed at Brighton Station, looking remarkably unimpressive next the the very grand looking stone water tower next to it! All this changed with the construction of Mocatta's station building in 1840, which forms the frontage of the station as it appears in the present day, albeit without the porte-clochere that houses the accessways and taxi rank.

The site of the station was constructed a little south-west of the site originally proposed by Mr. Rennie and was built on an impressive plateau carved into the hillside below Howard Place and Terminus Road. It was high up on the side of the valley through which London Road meandered out of the town and the goods sidings on the Eastern side of the station were actually 30 foot lower than the passenger lines.

Given the severity of the local geography, that is no mean feat: thousands of tonnes of chalk had to be removed to create an artificial plateau some 130 feet above sea level. This required a workforce of 3500 men and 570 horses.

The entrance to the station was reached from the top of Trafalgar Street (as it is today) and was bound on the town side by a tall brick wall. The station is, and indeed was, extremely central and it was proven to be the best location on hindsight, when compared to the other 4 plans. The short walk to North Street takes approximately 6 minutes and a further 4 minutes to reach the seafront. It follows that the only real complaints about the location were from a civil engineering point of view. Even today, the site remains easily accessible by road from East and South.

ABOVE: The entrance to Brighton Station, showing the bridge over Trafalgar Street.

They were originally reached by a connecting line, which left the Shoreham Branch just outside the terminus (with the junction facing towards Shoreham) and passed through a tunnel under a corner of the station site. This tunnel, a colleague has informed me, still exists today as a disused rifle range and forms part of an occasional Tour of the Station.

As if the Station's plateau construction were not enough, a train leaving the station would have immediately entered the massive New England Cutting before diving into the 231 yard long New England Tunnel and its onward journey. Originally Portslade Station was the halfway point and an engine repair shed was provided at the Brighton Station site.

ABOVE: This engraving shows a view of the New England Cutting, taken from The Brighton Herald’s coverage of the line’s opening. The octagonal building is a water tower for the locomotives, with the original train shed behind it. Photo owned by TheMadgewick Collection.

As has already been stated, little development occurred at that time between the outskirts of Brighton and Portslade Station. The view to the coast back then was considered to be very picturesque, taking in the sea on one side and pleasant countryside on the view inland.

At Kingston, the railway runs very close to both the road and the sea in a narrow pinch. This was considered a great convenience to shoreline traders who would be able to quickly and conveniently transfer their goods and at little expense. The railway included a wharf and sidings here, but there was a problem connecting them to the main line. The track would have to cross the road and the turnpike trustees of the day objected. Although the railway was advertised as carrying goods to and from the ports of Shoreham and Kingston from 24th August 1840, this did not occur until July 1841, by which time an agreement was reached with the turnpike trustees and a crossing was built. In later years the road was raised up so that it crossed the line on a bridge. The track to the wharves was connected to the track inland by means of turntables.

Before the Shoreham Railway was extended further west, there was an omnibus service between Shoreham and Worthing to cater for the onward journey. This service began on the 27th June 1840 and is still in continual use today as part of Brighton & Hove Buses' No.2 bus route.

The arrival of the railway in Brighton was watched with great interest from both sides of the English Channel. As has been stated previously, Brighton had very strong long standing communications with Dieppe in France. This is partly due to the excellent ferry connections at the Chain Pier, but another deeper and more significant reason is that, like Brighton, Dieppe is the closest seaside town to its capital city. During 1840, the Brighton Herald Newspaper published regular articles from its Dieppe correspondent with regard to the progress of rail travel towards Brighton.

At that time, the social scene in Dieppe was starting to pay considerable attention to accommodation for the steamer customers from Brighton, in anticipation of a time when both towns would be well served by railways. Theoretically, this would allow fairly easy travel between London and Paris. To this end, the Municipal Councils in Paris and Dieppe were encouraged whole-heartedly “to co-operate with their English neighbours to establish a packet system more worthy of plying on this station”.

Meanwhile, in Brighton there were fears that the Paris & Rouen Railway might not be extended to Dieppe. The Brighton Herald of 18th July 1840 wrote: “The construction of the Paris line to Dieppe is of the greatest importance to Brighton. Since by stopping the line at Rouen, the tide of passengers will be sent to Le Havre and so on to Southampton for their onward journey to London.” The London and Southampton Railway had been operating throughout these concerns, having opened wholesale on 18th May 1840. As a rival rail system, The London & Southampton Railway was not without its hiccups in its early days, which were reported with great relish by The Brighton Herald!

In the meantime, the London to Brighton line continued to plough southward with considerable progress, spurred on no doubt by news of the London & Southampton Railway’s success. On 18th July 1841 it had progressed as far as Haywards Heath and passengers were completing the (now greatly reduced) journey to Brighton by stagecoach, the whole trip being slashed to just 4 hours. Some of the coaches employed had been originally running the entirety of the route from London to Brighton so were possibly a little defensive towards their intending clients. New road links were created in connection with the trains between Lewes, Haywards Heath, Lewes, Uckfield, Maresfield and Eastbourne.

The first journey on the line was covered in the Brighton Herald thus: “The ride was performed in a manner to create the utmost confidence in its safety”. Also that “the advantages of this great work will be felt in the remotest parts of the country”.

Advantage was also expected across the channel in France as The Herald’s Dieppe correspondent had hopes that “the partial opening of the London to Brighton Railway (LBR hereafter) on Monday will soon cause us to be flooded with fashionable visitants”.

ABOVE: David Mocatta’s

Brighton Station building (albeit with a bit of artistic licence). This is the Brighton Station people know

today, but somewhat hidden behind the ornate port clochere over

the forecourt. (Image owned by Brighton History

Resource Centre).

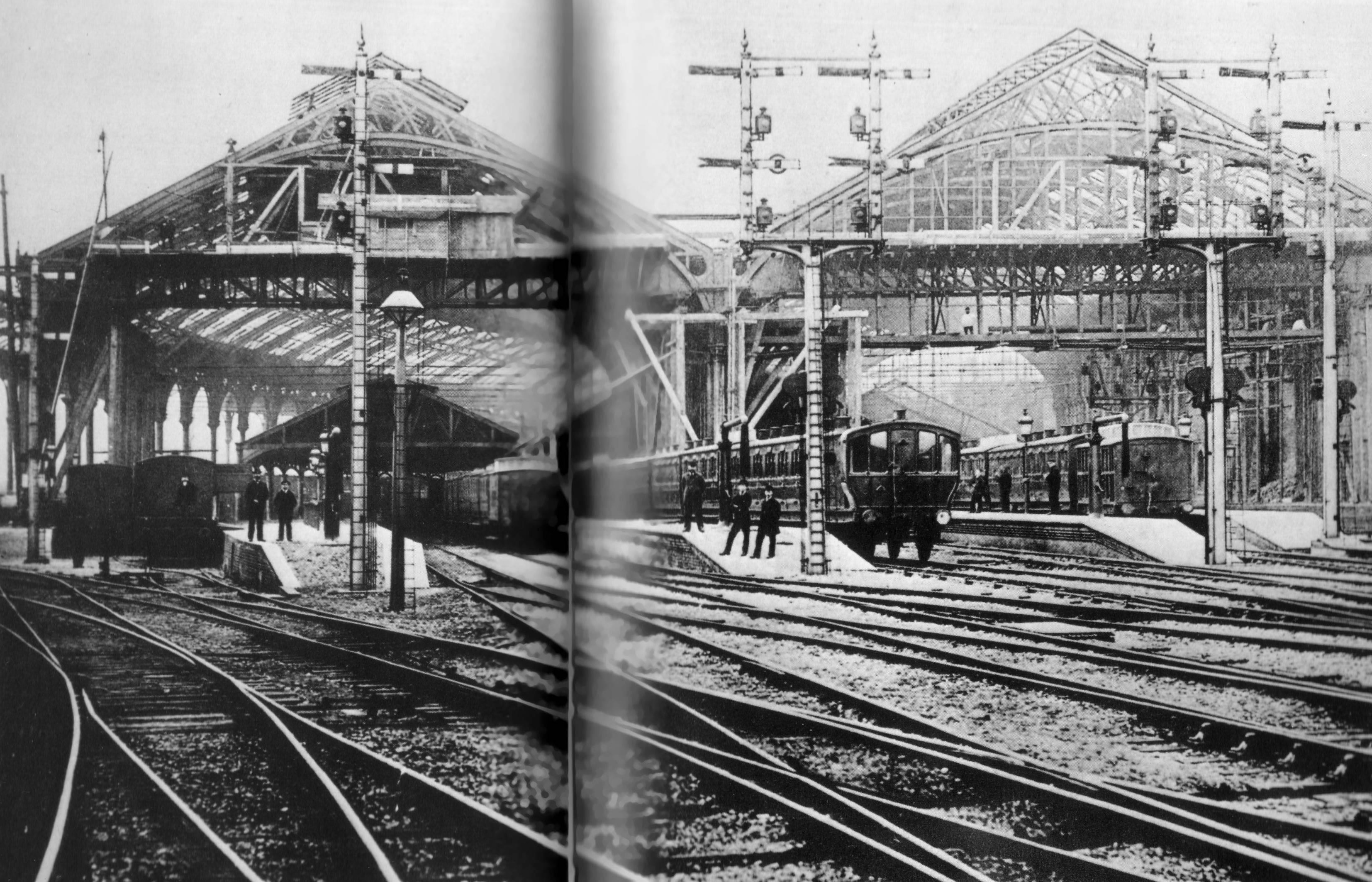

The 3 overall roofs, (250 foot long), were allocated with two for the London Line and one for the Shoreham Line. The original roofs were constructed of wrought iron principals supported by cast iron columns and girders. They were originally boarded over and covered with a slate roof. The fantastic and highly ornate canopies we see today were built to replace the (by then, ailing) originals in 1882/83 and Mr. Rastrick’s structures were dismantled.

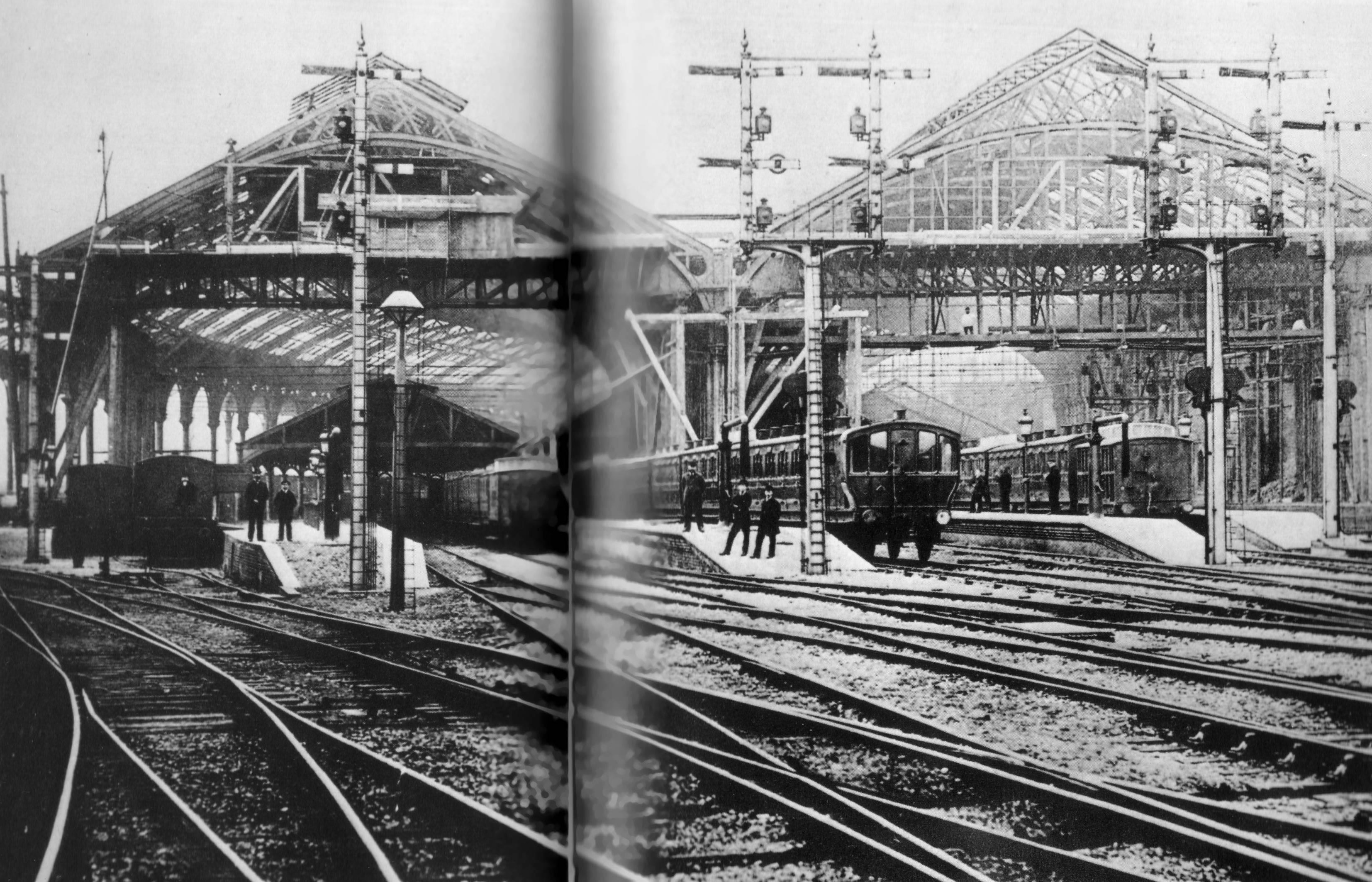

ABOVE: This photo shows the original train sheds underneath the new wrought iron rooves being constructed in 1882. The 3 overall roofs, (250

foot long), were allocated with two for the London Line and one for

the Shoreham Line. The original roofs were constructed of wrought

iron principals supported by cast iron columns and girders. They were

originally boarded over and covered with a slate roof. The fantastic

and highly ornate canopies we see today were built to replace the (by

then, ailing) originals in 1882/83 and Mr. Rastrick’s structures

were dismantled. (Image owned by The National

Railway Museum)

ABOVE & BELOW: Another two views of

the impressive roof structure. If the scale of the roof structure

were not impressive enough, the whole structure has a gentle curve

throughout its length. (Images owned by National

Railway Museum - top / Chris Horlock - bottom).